The term, convulsion or seizure, denotes a temporary disturbance of brain function manifested by involuntary motor, sensory, autonomic or psychic phenomenon, alone or in any combination. Some change in sensorium is usually present. Though a wide variety of CNS disorders can cause convulsions, the fundamental defect remains irritation of the CNS in each one of them.

Convulsions are relatively more common in infancy and childhood than at any other period of life, the peak incidence occurring during the first 2 years. The overall incidence in childhood is stated to be 8%, among mentally retarded children (except those with Down’s syndrome) 20%, and among those suffering from one or the other type of cerebral palsy 35%. In a retrospective study, we found an overall incidence of 15% (inpatients) and 11% (outpatients) in the Govt. Children Hospital, Jammu.

Clinical workup must, in the first place, clarify if what has been described as convulsion is indeed convulsion or not. Disorders simulating recurrent convulsions include breath-holding spells, narcolepsy, abdominal epilepsy, hysterical fits, syncope, apneic spells and migraine

In the newborn, it is infrequent to see convulsions in the form of typical tonic-clonic movements. On the other hand, such apparently minor manifestations as twitching, conjugate deviation of eyes, hypertonus in a twitching limb, irregular jerky movements and nystagmus, startling, pallor and hypotonia, slow and irregular respiration with periods of apnea and feeble cry, and cyanotic attacks may well mean convulsions.

Symptomatic enquiry should include all the details about the attack: Was the onset sudden or gradual? Were the convulsions local or generalized? Where did they begin? In which fashion did they progress to rest of the bodily parts? Did the child micturate or defecate during the attack? How long did the attack last? Was there fever preceding or following the attack? Did he sleep after the attack? Or, did the attack lead to headache, automatism or paralysis? Any associated manifestations like neck stiffness, vomiting, behavioral problems, or discharging ear?

In case of recurrent convulsions, ask the attendants to give a clinical account of the first attack and the age at which it occurred. What is the minimal and maximal gap between the attacks? Is there any aura preceding the attack? Does the attack ever occur during sleep? Does the child bite his tongue, injure himself, micturate or defecate during convulsions? Does he lose consciousness? Are there any such manifestations as persistent headache, automatism or pseudoparalysis (Todd paralysis) after the episode?

In recurrent convulsions secondary to organic brain damage, you must look for evidence of such conditions as tuberous sclerosis, hydrocephalus, Sturge-Weber syndrome, cysticercosis, toxoplasmosis, syphilis, mental retardation, cerebral palsy, etc.

CONVULSIONS IN THE NEWBORN

You need to consider the following conditions when encountering convulsions in the newborn:

First and second day: Perinatal problems such as birth injury, asphyxia, hypoxia, intracranial (especially intraventricular) hemorrhage; drug withdrawal syndrome; pyridoxine dependency; accidental injection of anesthesia into baby’s scalp during labor; inborn errors of metabolism such as phenylketonuria.

Third day: Hypoglycemia

Fourth day and onwards: Fulminant infections such as septicemia, meningitis; hypocalcemic tetany, hypo- or hypernatremia, hypomagnesemia; kernicterus; tetanus; congenital malformations like arteriovenous fistulae, pomocephaly; intrauterine infections like toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalic inclusion disease, herpes simplex (TORCH/STORCH).

Perinatal Problems

Birth trauma, following difficult delivery, may result in anoxia together with cerebral edema and microhemorrhages in low birth weight newborns and massive hemorrhages in mature babies. In the former situation, convulsions may present as tonic spasms preceded by some clonic jerks on first day only. In the later situation, convulsive manifestations usually appear between 2 to 7 days of birth. These are unilateral and are accompanied by retinal hemorrhages, dyspnea, bulging anterior fontanel, skull fracture and cephalhemaloma, and blood-stained or frankly bloody CSF.

Hypocalcemia

Hypocalcemic tetany, the most common biochemical cause of neonatal convulsions, occurs usually in babies on cow’s milk formula rich in phosphates. Manifestations occur either on first day or about the seventh day of birth. These include, besides convulsions, jitteriness, laryngeal spasm, tremors, muscular twitching and carpopedal spasm. The infant remains all right in between the attacks.

Serum calcium is invariably under 8 mg% and phosphorus high. Intravenous administration of calcium gluconate (5 to 10 ml of 10% solution) leads to dramatic response.

Hypoglycemia

Convulsions due to hypoglycemia are likely to occur in infants who suffer from intrauterine growth retardation, in infants of toxemic mothers, in infants of diabetic or prediabetic mothers, in smaller of the twins, and in infants with idiopathic respiratory distress syndrome, kernicterus, Beckwith syndrome, infections, adrenocortical hyperplasia and glycogenosis.

Manifestations include, besides convulsions, tremors, twitching, cyanosis and apneic spells.

Blood glucose level is under 30 mg% in term infants and 20 mg% in preterm ones.

Infections

Pyogenic meningitis as such or as a complication of septicemia is an important cause of neonatal convulsions. The most common complaint is that the infant is just not well with refusal to feed, lethargy, irritability and restlessness. Umbilicus is often septic. Neck stiffness is usually absent and anterior fontanel may or may not be bulging. Lumbar puncture is essential to establish the diagnosis.

Tetanus is likely to occur in newborns in whom umbilical cord is cut under septic conditions and mud, dung or such other harmful substances are applied to the navel at birth or soon after it. It usually manifests at 5 or 6 days after birth with difficulty in sucking, stiffness of jaws, and generalized spasticity, spontaneously or in response to external stimuli. Risus sardonicus is a classical manifestation

Malaria in neonatal period, though rare, may manifest with convulsions either on account of cerebral involvement or hyperpyrexia.

Pyridoxine Dependency

The newborn of a mother who has had prolonged administration of pyridoxine during pregnancy may develop convulsions which are resistant to various treatments. Such a pyridoxine dependency may also occur in newborns suffering from a hereditary metabolic defect leading to unusually large needs of pyridoxine.

The infant is restless between convulsive attacks, reacting to external stimuli (acoustic and mechanical) with twitching. He blinks the eyes, moving in an uncoordinated fashion.

A dramatic response to a 25 mg dose of pyridoxine is a rule.

Drug Withdrawal Syndrome

The newborn of a mother addicted to narcotics (morphine, heroin) or alcohol is prone to develop withdrawal symptoms which include convulsions, irritability and excessive drooling.

Accidental Injection of Anesthesia

During labor, as the mother is being given paracervical block, baby’s scalp may be accidentally injected. Such a newborn develops intractable convulsions.

Electrolyte Imbalance

Both hypo- and hypernatremia, following dehydration or its incorrect treatment with parenteral fluids and electrolytes, may cause severe convulsions with permanent neurologic damage.

Hypomagnesemia

A newborn with convulsions associated with established hypocalcemia not showing response to calcium therapy must arouse suspicion of hypomagnesemia.

Metabolic Disorders

You must consider possibility of an inborn error of metabolism if convulsions are resistant and there is a history of such a disorder in the family.

Galactosemia is characterized by occurrence of convulsions following ingestion of milk. Presence of jaundice and hepatosplenomegaly supports the diagnosis.

Fructose intolerance is characterized by occurrence of hypoglycemic convulsions or coma immediately after ingestion of such foods as contain fructose, say carrot, fruits juices, milk formulas containing sucrose, or cane sugar.

Maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) is characterized by hypoglycemic convulsions in association with feeding difficulty, marked metabolic acidosis, progressive neurologic and mental deterioration and odor of maple syrup in urine.

Congenital Malformations of CNS

A newborn presenting with convulsions and facial asymmetry, microcephaly or any other obvious malformation should be suspected of an underlying developmental defect of CNS, say arteriovenous fistula, congenital hydrocephalus, porencephaly, microgyria, corpus collosum agenesis or hydrancephaly.

The newly-recognized entity, Aicardi syndrome, is characterized by trio of infantile spasms resistant to therapy, chorioretinopathy and agenesis of corpus callosum. Additional features include mental retardation and vertebral and costal abnormalities. Its cause appears to be a newly-mutated Xchromosomal-dominant gene lethal to males in utero. Naturally, all patients are females. Prognosis is poor, most subjects dying in early life.

Drugs

If mother has had large doses of phenothiazine(s) as a part of management of toxemias of pregnancy, the newborn may suffer from phenothiazine poisoning. Though jitteriness is the most common manifestation, he may have convulsions with generalized spasticity including opisthotonos. Such drugs as nikethamide, administered for neonatal asphyxia, if given even in a marginally higher than the recommended doses, may be responsible for convulsions.

CONVULSIONS IN LATER INFANCY AND CHILDHOOD

Acute (Nonrecurrent) Convulsive Disorders

Febrile Convulsions

The term refers to seizures occurring at the onset of acute extracranial infection or in association with high environmental temperature.

This is the most common cause of convulsions between 6 months to 3 years of age. Outside this age range, it is infrequent to have febrile convulsions. Boys are affected nearly twice as frequently as girls. Family history of convulsions, and higher incidence in twins and children born of consanguinous unions are noteworthy.

The remaining salient features of the condition are:

- It is usually associated with rapid rise in body temperature. There is, therefore, preceding history of the child having been unwell a few hours prior to the onset of convulsions.

- Generalized rather than focal convulsions are nearly a rule.

- The attack lasts less than 10 minutes and in no case more than 20 minutes

- There is no recurrence before 12 to 18 hours of the attack accompanying rapid rise of body temperature.

- There is no residual paralysis of a limb following the attack

- CSF after the attack is normal.

- EEC after the attack is normal. Convulsions associated with fever (not of CNS infection) but not satisfying the above criteria are often labeled “atypical” rather than “typical” febrile convulsions. This condition is now considered a precursor of idiopathic epilepsy.

CNS Infections

Pyogenic meningitis may manifest suddenly with convulsions in association with high fever, restlessness, irritability, vomiting, headache and neck stiffness. Cranial nerve palsies and papiledema are present in some cases. The presence of a generalized purpuric rash points to meningococcal meningitis.

Encephalitis manifests with change in sensorium (varying from lethargy to coma), fever and vomiting in addition to convulsions. Whereas an infant may show gross irritability, headache is a common symptoms in older children. Remaining manifestations may include peculiar behavior, hyperactivity, altered speech and ataxia. There is rapid variation in the clinical picture from hourto-hour.

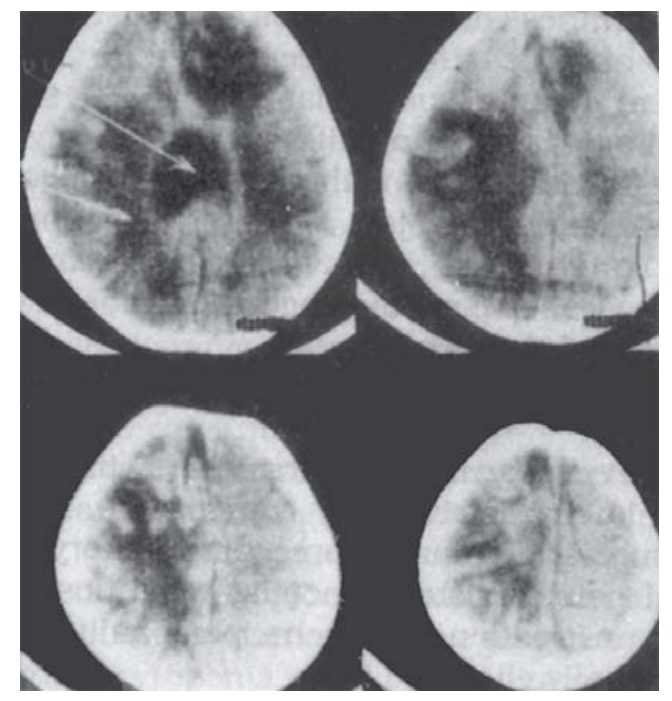

Cerebral abscess (Fig. 12.1) is characterized by headache, vomiting and visual disturbances from high intracranial pressure, focal neurologic manifestations such as convulsions, cranial nerve palsies, ataxia, visual field defects and hemiparesis from local pressure, high or low irregular fever, chills, rigors and leukocytosis

Fig. 12.1: CT scan showing multiple cerebral abscesses in an infant suffering from suppurative otitis media (SOM).

from toxemia, and irritability, behavioral problems, drowsiness, and weight loss from intracranial suppuration. The presence of a septic focus such as otitis media, lung abscess, empyema, bronchiectasis, infective endocarditis, orcyanotic congenital heart disease lends support to the diagnosis.

Cerebral malaria, a life-threatening complication of Plasmodium falciparum infection, is characterized by meningeal signs, convulsions and coma. CSF is more or less within normal limits.

Toxic Factors

Tetanus has a sudden onset with muscle spasm and cramps, particularly about the location of inoculation, back and abdomen. In the next 48 hours, clinical picture worsens. Neck rigidity, positive Kerning sign and trismus become prominent. The face assumes atypical expression, “risus sardonicus”, which consists of clenching of jaws, laterally-drawn lips and raised eyebrows. There is increasing stiffness of upper limbs and legs. The former are kept flexed and the latter hyperextended.

A typical tetanic spasm lasts 5 to 10 seconds and consists of agonizing pain, stiffness of the body which gets almost arched backward with retraction of head (opisthotonos) and clenching of jaw. As the disease progresses, a very simple stimulus also precipitates an attack. In advanced cases, spasms may become almost a continuous and constant phenomenon.

High fever is uncommon but a low grade fever is usually present.

Lead encephalopathy, occurring late in the course of plumbism is characterized by convulsions, high intracranial pressure and coma. A preceding history of transient abdominal pain, resistant anemia, weightloss, irritability, vomiting, constipation, headache, personality changes and ataxia is usually elicitable.

A lead line over the gums is characteristic of plumbism. Urine lead level of over 80 mcg/d/24 hours is diagnostic. Shigellosis, which usually manifests in the form of bacillary dysentery, may also cause in one in 10 subjects convulsions together with such CNS symptoms as headache, delirium, neck stiffness and fainting.

Nontyphoidal salmonellosis, though commonly a cause of gastroenteritis (particularly the outbreaks occurring in late summer and early fall), may also be responsible for very high fever, headache, confusion, change in senorium, meningismus and convulsions.

Anoxia

Anoxic state, as a result of such factors as inhalation anesthesia or sudden severe asphyxia, may cause convulsions.

Biochemical Defects

Hypocalcemic tetany in the postneonatal period occurs in subjects suffering from such predisposing conditions as vitamin D deficiency rickets, malabsorption syndrome, alkalosis or hypoparathyroidism which may be idiopathic or secondary to operative damage in thyroidectomy done for thyrotoxicosis. The diagnosis of tetany associated with rickets is not difficult. The patient shows usual evidence of rickets such as delayed closure of anterior fontanel, rachitic rosary and widening of wrists. X-ray wrist shows cupping, fraying and fragmentations of the epiphyseal ends of radius and ulnar and increased distance between the epiphysis and carpal bones. Senim alkaline phosphatase and phosphorus are elevated. Serum calcium is low. In idiopathic hypoparathyroidism, tetanic convulsions occur in infants suffering from defective dental enamel, brittle nails, cataract, recurrent diarrhea susceptibility to fungal infection, hypocalcemia and hyperphosphatemia. This combination is named DiGeorge syndrome. Remarkable lymphocytopenia and immunologic deficiencies constitute its hallmark. In another form of idiopathic hypoparathyroidism, hypocalcemic convulsions are superimposed on such associations as short stature, mental retardation and shortening of the ulnar metacarpal bones so that the index finger becomes the longest finger. This form is tended pseudohypoparathyroidism. Hypomagnesemia tetany must be suspected if in spite of adequate therapy with calcium, the patient’s hypocalcemic state fails to respond clinically, biochemically or both. Hypoglycemia in the postneonatal period may be due to insulin overdose, hyperplasia of islets of Langerhans, hypopituitarism, adrenocortical insufficiency, liver disease, glycogenoses or fractose intolerance. Manifestations include early morning convulsions preceded by pallor, sweating and weakness.

Electrolyte Imbalance

Hypo- or hypernatremia, usually in association with dehydration or its careless correction, may cause convulsions even in later infancy and childhood as in neonatal period.

Cerebral Edema

Convulsions may complicate the clinical profile in a child with acute nephritis, burns or allergic edema of the brain. The development may well be related to cerebral edema.

Drugs

A large number of drugs are suspected of causing convulsions. The list includes phenothiazines, aminophylline, antihistamines, acetazolamide, diphenoxylate, strychnine, propoxyphenes, hexachiorophene, steroids, amitryptalline, amphetamine, imipramine, pyrimethamine, chloroquine, carbamazepine, nalidixic acid, metoclopramide, and isoniazid.

Chronic or Recurrent Convulsive Disorders

Epilepsy

The term refers to “various symptom complexes characterized by recurrent, paroxysmally attack of unconsciousness or impaired consciousness, usually with a succession of tonic or clonic muscular spasms or other abnormal behavior”. It may be organic (secondary or symptomatic) or idiopathic.

Organic epilepsy: It is frequently accompanied by cerebral palsy, mental retardation and ECG abnormalities. Various conditions that may cause it are:

- Post-traumatic: Direct damage to brain tissue

- Posthemorrhagic: Injury to brain at birth or afterwards, bleeding diathesis, rupture of miliary aneurysm, pachy meningitis

- Postanoxic: An after-effect of severe neonatal asphyxia

- Postinfectious: Meningitis, encephalitis, cerebral abscess, sinus thrombophlebitis

- Post-toxic: Kernicterus, chronic poisoning with lead, arsenic, etc.

- Postmetabolic: Hypoglycemic brain damage

- Degenerative: Intracranial neurofibromatosis, cerebromacular degeneration, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE)

- Congenital: Arteriovenous aneurysm, Sturge-Weber type of vascular anomaly, cerebral aplasia, porencephaly, hydrocephalus, tuberous sclerosis

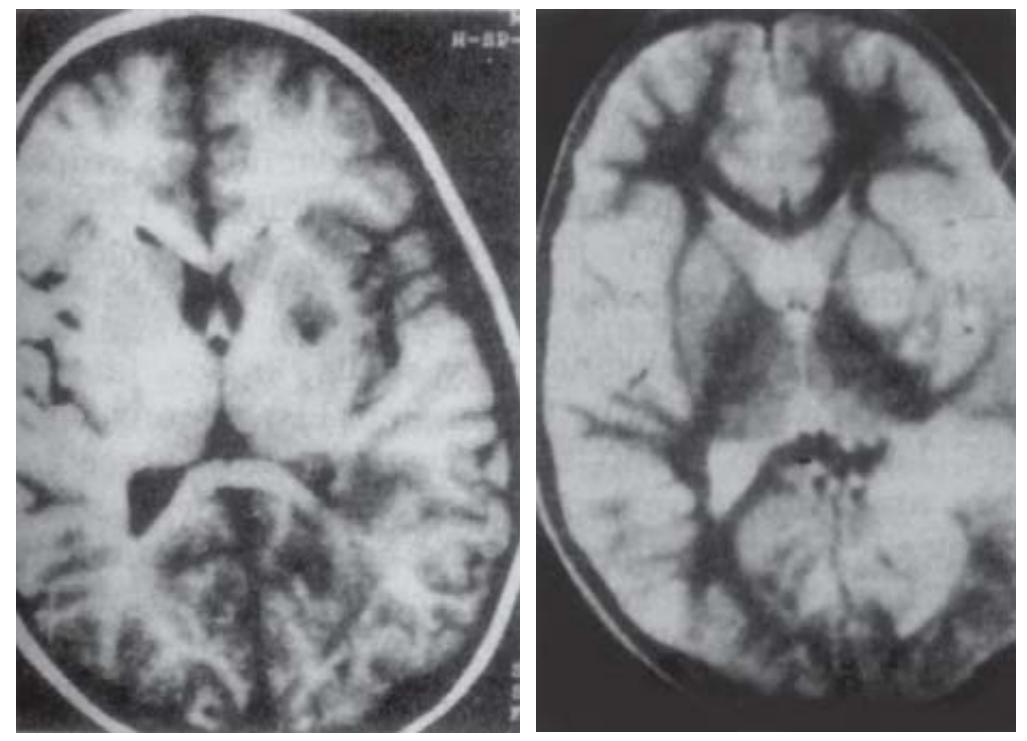

- Parasitosis: Cysticercosis (Fig. 12.2), hydatid disease, ascariasis, toxoplasmosis, syphilis.

Idiopathic epilepsy: Also called cryptogenic, primary, essential or genuine epilepsy, it may be of genetic or acquired type. Grandmal epilepsy is characterized by generalized tonic-clonic convulsions which are predominantly tonic during infancy. The attack in one-third cases preceded by an “aura”, manifests suddenly. During the tonic phase, lasting less than 20 to 40 seconds, the child usually loses consciousness. His face becomes pale and gets distorted with rolling of the eyeballs upward or to one side. The pupils dilate and corneas become insensitive to touch. The head is thrown backward or to a side. Rapid contraction of jaw muscles

Fig. 12.2: Neurocysticercosis MRI, T1- and T2-weighted axial images, showing degenerating parenchymal cysts.

may cause biting of the tongue. Rapid contraction of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles may force the air out of the lungs through the closed glottis, causing a characteristic “starving cry”. Rapid contraction of abdominal muscles may cause micturition, and less often, even defecation. As the tonic phase progresses, inadequate respiration results in cyanosis.

The clonic phase, which may not be quite perceptible in infancy, follows tonic phase, lasting over a variable period.

After the attack, the patient usually sleeps. The post-convulsive sleep is followed by the so-called “postictal reactions” in the form of confusion, headache and stupor. Occasionally, todd paresis/ paralysis (usually for 12 to 24 hours but infrequently for a week or so), and prolonged automatism may follow.

Petit mal epilepsy (absences, dizzy spells, lapses, fainting turns) is characterized by brief transient loss of consciousness, lasting up to 30 seconds, without any preceding aura, any convulsive movements or any postictal sleep. Classically, a child, busy in writing or reading, suddenly stops the activity, resuming it after the attack is over in some seconds, usually less than 20 to 30 seconds. During the attack, he is likely to drop the pen or notebook held in hand. Falling on ground, as in the case or grand mal seizures, is rare. The child is usually unaware of the attack. Factors that precipitate an attack include exposure to blinking light and hyperventilation. The frequency may be one or two episodes a month, or hundreds of them a day.

Typically, petit mal seldom occurs before the age of 3 years and often settles without any treatment by puberty. The peak incidence in childhood occurs between 4 to 8 years. The incidence in girls is higher than in boys.

EEG shows a characteristic 3 per second spike and wave pattern. Focal epilepsy, though usually of postorganic origin, may occasionally be idiopathic. It may be sensory or motor, the latter being the dominant variety seen in childhood.

In the motor variety, called Jacksonian epilepsy, convulsions are typically clonic, involving muscles that are usually brought into action or voluntary movements. Thus, hands, face and tongue are more frequently affected than feet and trunk. By the term “Jacksonian march” is meant that focal convulsions in a particular part progress too others in a fixed pattern. For instance, convulsions beginning in thumb would spread to fingers, wrist, arm, face and leg on the same side in this fixed order. A point meriting mention is that, in focal epilepsy, consciousness is usually not affected unless, of course, when its spread is rapid and extensive.

Psychomotor epilepsy (temporal lobe epilepsy) is characterized by visceral symptoms like nausea, vomiting or epigastric sensations, followed by short period of increased muscular tonicity and, later, semipurposive movements during a period of impaired consciousness or amnesia. Vasomotor manifestations such as circumoral pallor are frequently present. Some children may have slight aura in the form of a “shrill cry” or an indication for “help”. The episode usually remains for 1 to 5 minutes. The postictal period is often marked by a brief spell of sleep or drowsiness. Thereafter, the child resumes normal activity

EEG is often normal, except during the episode of seizure. Infantile myoclonic epilepsy (infantile spasm, salaam seizures, lightning major, jacknife epilepsy, West syndrome) is characterized by massive attacks of sudden dropping (flexion) of the head and flexion of the arms, once or as many as several hundred times a day. The affected child is under 2 years of age, usually under 6 months. Significant developmental as well as mental retardation is more or less a rule in both primary (seizures occurring before 4 months or developmental level low right from beginning as in congenital cerebral defect) and secondary (following unrecognized encephalitis or an underlying defect in cerebral metabolism) types.

EEG changes are in the form of random high-voltage slow waves and spikes, suggesting a disorganized state. Hypsarrhythmia is the name given to this EEG pattern.

Epilepsy-Simulating States and Epileptic Equivalents

Narcolepsy

This disorder, simulating epilepsy, occurs only rarely in childhood. Boys suffer more often than girls. The attack is characterized by diurnal episodes of irresistible sleep, usually precipitated by sudden emotional upheaval. The patient, while working, talking, swimming, driving or walking, suddenly stops activity and falls asleep. The sleep is shallow and he can easily be aroused. After waking up, he is quite alert.

Narcolepsy usually becomes chronic though spontaneous cure, or, at least, improvement occurs more often in it than in the case of true epilepsy.

Hysteria

Also called hysterical fits or psychogenic epilepsy, the condition occurs in children usually above 6 years, with a typical neurotic background. During the attack, such characteristic features of true epilepsy as dilation of pupils, pallor of skin and mucous membrane, true loss of consciousness, loss of sphincter control and bodily injury are absent. Further, the attack lasts fairly long (half-an-hour or so) and during its course the patient exhibits bizarre crying, moaning and irrelevant talk.

Breath-Holding Spells

This common condition of early childhood with onset between 6 to 18 months of age is sometimes accompanied by tonic and clonic convulsions in which case differentiation from true epilepsy becomes essential. First, in breath-holding spells, an obvious precipitating factor such as a disciplinary conflict between the child and the parents (which may manifest in one or the other form) can invariably be elicited. Secondly, cyanosis in spells precedes convulsions whereas in epilepsy it appears after the convulsions have progressed. Thirdly, EEG in spells is invariably normal.

Syncope

Simple fainting spell, often complicated by tonic and clonic convulsive reactions involving face and arms, may follow a pinprick, a sudden fright or some such situation, provided that the child is in sitting or standing position. Such a subject has a defect in reflex regulation of the vascular system. As a result, with precipitation from one of the factors, sudden relaxation of the visceral venous system occurs, leading to bradycardia and hypotension. Note that if you have the child lie flat on table, or if you make him cry vigorously before and during a minor surgical procedure such as drawing a blood sample, chances are that he would not have fainting spell.

Remaining causes of fainting, chiefly due to transient cerebral anemia, include hyperventilation in upright position, StokesAdams syndrome, paroxysmal tachycardia, hyperactive carotid sinus reflex (as in sick sinus syndrome resulting from myocarditis or cardiac surgery), posterior fossa tumor, cough syncope (as in asthma) and extension of neck in a child with fused cervical vertebrae.

Migraine

Some authorities regard migraine as a variant of epilepsy on account of its episodic nature often preceded by an aura, its chronicity, its genetic features, its occurrence in association with epilepsy in the same family, and occasional replacement of migraine by typical epilepsy in due course.

FURTHER READING

- Bains HS, Mittal S. Febrile seizures. In: Gupte S (Ed): Recent Advances in Pediatrics (Special Vol 18: Pediatric Neurology). New Delhi: Jaypee 2007:334-340.

- Malik Gk. In Gupte S (Ed): Recent Advances in Pediatrics (Special Volume 18: Pediatric Neurology). New Delhi; Jaypee 2008:341-356.

- Greydanus DE, Van Dyke DH.Epilepsy in adolescents. In: Gupte’S (Ed): Recent Advances in Pediatrics (Special Vol 19: Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics). New Delhi: Jaypee 2007:300-339.

RELATED POST

Empyema Thoracis

Bell Palsy (Peripheral Facial Palsy)

Opportunistic Infections